Fragments of/on process

This piece was originally written for Next Wave’s arts journalism training programme, Text Camp.

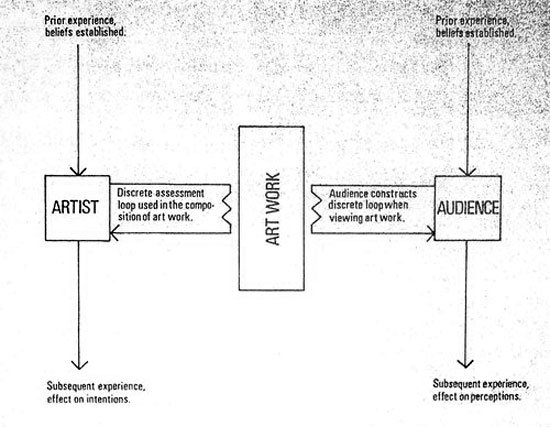

Stephen Willats’s Model of an Existing Artist-Audience Relationship, 1973 Published in the book The Artist as an Instigator of Changes in Social Cognition and Behaviour (London: Occasional Papers, 2010 [1973]), 28. Also found in Grant Kester’s The Device Laid Bare: On Some Limitations in Current Art Criticism”, e-flux journal No 50.

This is a short text in six moments that offers up fragmented thoughts on critical process.

Moment 1 (Encounter)

Artist Willem De Kooning spoke of the content of a work of art as “a glimpse of something, an encounter like a flash.” For him, content was “very, very tiny”, something both intimate and invisible.

As a critic, content is your referent; it’s that which you try and tease out of an experience that is multiple, complicated, affective, perhaps poetic. As Umberto Eco explored in Poetics of the Open Work, content is that which is opened within a work. It is that which enables you to engage in a conversation with it.

Moment 2 (Resistance)

The intellectual tradition of criticism, particularly under the guise of the market economy, posits that criticism takes two iterations: the moment of your encounter with the work, and the articulation of your own thinking about the work that takes place in the form of, most often, a text.

This is a very linear understanding of how critics- and people in general- think about works of art. It assumes that this thinking is particularly focused from the onset; that it is gathered in the moment of encounter and simply shaped into a form in the text itself. Yet as Hannah Arendt has stated in her unfinished work The Life of the Mind, “thinking is always out of order, interrupts all ordinary activities and is interrupted by them. The oddities of the thinking activity arise from the fact of withdrawal. [..] Thinking always deals with absences, and removes itself from what is present and close at hand.”

Moment 3 (Articulation)

I want to briefly complicate this tradition of identifying the critical process in two simple stages, building on what Arendt offers to us here. We can perhaps consider that as critics, we are both present and removed; in our thinking, we are negotiating a myriad of forces of knowledge, emotion and intent that shape our perception of a work, our articulation of it, and the interpretation that is fuelled by that.

Criticism is not simply a work of beginnings, neither is it one of conclusions. We do not simply ignite or derive, we propose, question, position and engage ideas. We make certain moments of content appear on the page.

So I propose that we consider a more complex set of events in our process of criticism; I propose that:

- this begins before our encounter with work

- it continues after in our formation of memories, our note-taking, our research and attempt to define and delineate through old and new knowledge

- it emerges in a process of interpretation in which we, sometimes less consciously than we would like, try and give shape to our thoughts.

- it develops in the form of a text, in which several forces are at play: the intent, the space, the timing, the deadline, the context, the relationship.

- then it continues on, once that text itself is released. Let’s say it dissipates into the public sphere.

Moment 4 (Interpretation)

In some ways, criticism is a conflict with meaning. We excavate our thoughts to be able to justify and identify moments of that encounter with a work of art. Through interpretation we both ascribe meaning and try and make sense of our intuitive responses.

Thinking about process can help differentiate between what is intuition, what is knowledge and what is judgment. We can consider the ways in which a work might appear, in which a fragment can be described or teased out.

Yet interpretation can be controlled too; where you write, how you approach that writing, and how you trigger different memories are essential to being able to shape and structure your own thinking.

Moment 5 (Dialogue)

The text is the manifestation of our interpretation, and in some ways, the first dialogue that you might begin with your readers and the work itself. Although there are many ways to approach structuring a text, it’s also important to be aware of the ways in which the text tries the shape the writing.

Sometimes playing with structure to begin with might provide some interesting moments, recall some particular memories, or allow you to make connections that you haven’t encountered in your journey of interpretation.

Being aware of the assumptions you are making for what the text should be, is also crucial; allow your own thinking to dictate form. Consider the role of description in the text, and what is can enact. Then think about the action of a critical sentence, and where that should be positioned. In between will be your argument.

Any text is plural, and it has an odd quality of both distinction and equality. And, to return to Arendt, “with word and deed we insert ourselves into the human world.” So for a more aware, open-ended text, an awareness of criticism as a particular form of composition and conversation might be imperative. After all, this is merely an invitation, an extension; and the rest follows.